White People Need to Call Themselves Racist

- Kyrai Rose, Ph.D.

- Nov 25, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 30, 2025

I recently attended a film screening at our local high school that was hosted by the diversity and inclusion office of the school district. The film was titled, “I’m Not Racist…Am I?” The film followed a group of racially and economically diverse teenagers through a series of race and racism education initiatives and tracked the progress of their racial identity development.

Prior to the film, the director, Catherine Wigginton Greene, introduced herself and invited audience members to consider what they were feeling while watching the film and come up with one word that could encapsulate that feeling. The film was followed by a discussion facilitated by the director. She asked us to share what our word was and then share something about why we chose that word.

I had been in these types of discussions many times over the years, and I was bracing myself for what I have come to know as typical responses for white people who attempt to engage in conversations about race but are stuck on what I will call a “wrong focus.” At the same time, we are part of a movement that will not be complete in our lifetimes, and we have to keep showing up and make space for learning. This isn’t always easy, but it is necessary. I appreciate when the learning needs of unaware White people don’t overshadow the presence and voices of Black and Brown people in the space. I wasn’t sure what to expect from this group. We were in Eugene, Oregon, which is a very white place, and feels a lot like Kentucky in that when you step one foot outside the liberal cities, it is as conservative as you can imagine. Segregation is alive and well here in the Pacific Northwest.

Someone started with, “uncomfortable.” After that several white adults spoke about their shock and discomfort with the portion of the film that discussed the teaching that racism is discrimination added to societal power, and therefore, all white people are racist. They also discussed the distinction between bigotry and racism, explaining that people of color can be bigoted but not racist based on their definition (which is the definition most widely acknowledged in research and literature related to race).

I found myself feeling two things simultaneously: unsurprised and frustrated.

Unsurprised because the most typical focus for white people in conversations about race and racism – to struggle with the idea that they might be racist. Frustrated because it would be nice to be in a conversation about race and racism in which most white people could just say, “Yes, I was absolutely conditioned to be racist, just like every other white person in our country. Racism is our default setting – and the only solution is active anti-racism.” This is not to say that I expect that right now from all of us white folks. I was not always there! It was experiences and learning and growth that woke me up and helped me gain comfort with the reality of my conditioned racism. (My frustration is not a judgment nor an expectation-perhaps just a wish for movement and progress and collective healing)

I thought to myself, white people need to start calling themselves racist.

We have to get comfortable with that. We have to own it, and be the ones to keep owning it. We have to be the ones connecting the lines between our current privileged lives and the history of race and racism in our country. There is so much energy spent on getting white people to see this and admit it let alone own it and name it in ourselves. Instead of waiting for others to call us racist or instead of defending ourselves – why not just be the ones to say it?! I ask this question, but I already know the answer. To be the ones to say it would mean white people would be the ones responsible for their anti-racism journey. They would have to be the ones spurring their own motivation to dismantle the conditioning in themselves through active, intentional learning and growing. A lot of us white people leave that work to be done by BIPOC folks. We wait for it to be hand-fed to us rather than seeking to look more closely for our own reasons and to uphold our own values.

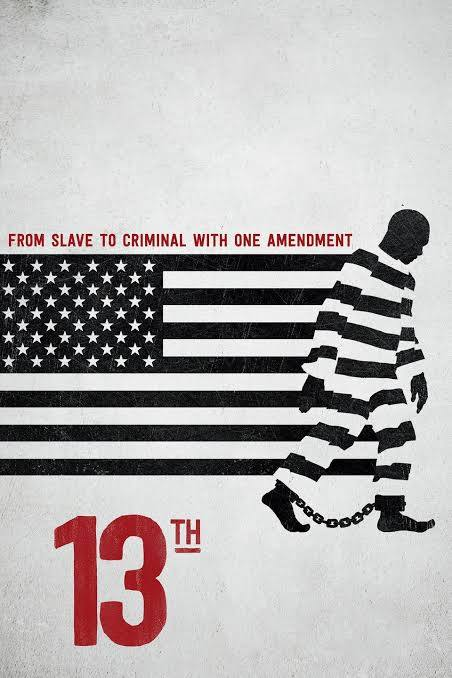

In order to take responsibility for our own racist ways of moving in the world due to our conditioning, we have to see it. And in order to do that we have to struggle with our conditioning. And in order to do that we have to wake up from the sleep of privilege…and in order to do that we have to stop being afraid that being racist by default as a white person makes you a “bad person.” And in order to do that, we have to see how much our fragility keeps us from joining in the work of dismantling white supremacy. And in order to do that we have to care about it enough to be uncomfortable. WE HAVE TO CARE ABOUT IT. This reminds me of a professor I had in my doctoral program, Dr. James Croteau. He always emphasized that in order for White people to do anti-racist work they have to have their own personal investment that comes from seeing the ways that white supremacy costs them. As long as racism is about other people, white people will perpetuate white supremacy by keeping themselves out of the equation. What if, instead, we took the energy we usually spend on trying to prove we or something else are not racist-and directed it toward anti-racism efforts? Read a book, watch a film, do some journaling about what you learned about race growing up and how that informed your unconscious ideas about people.

Let’s talk about values for a moment. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) holds as a main tenet that our quality of life improves when we live in alignment with our values. Values can be thought of as markers of being on the right track. Sounds simple enough. Know what feels fulfilling and important and live by that. If only it were that simple. How many people know their values, really? How many people have stopped to think about what is most important and assessed their lives to see if they really live in alignment with that?

Positionality: Our perspectives (what we see or don’t see; what we know or don’t know) are based on our positions within the social hierarchy (DiAngelo, 2016).

What about when values become confused with signals of positional safety? For example – if a person says they value equality and yet they deny their own racialized privilege…they are valuing their own personal safety constructed by positionality above their actual stated values. In the moment, feeling comfortable outweighs living in alignment with the value of equality. And typically, people will travel very far down the road of denial to stay comfortable – even if it means living out of alignment with their values. This can be seen in a plethora of ways among us white people. For example, dismissing BIPOC expressions of experiences with racism by criticizing the delivery and keeping the focus off the message. So, instead of hearing the pain and frustration behind being mistreated and responding in a humanizing, humble way, many white people instead focus on whether the person delivering the message was “angry” or how they said what they said. They can hide behind the idea that they are aligned with values of kindness or “the golden rule,” but really it is a hiding place that protects the comfort of the white person’s position by deflecting attention away from their racist behavior. This reinforces a conditioned idea of superiority for the white person and prevents any kind of connection between them and the person expressing their experience with racism. Choosing to focus on and defend the surface layer of such interactions, reducing them to a positionality rule book, prevents the authentic meeting of people. The words and feelings that humanize us are stopped at the door, so to speak, and comfort zones are mislabeled as values.

This is the pathology of privilege. Without realizing it, the white person is living in alignment with positioned privilege above all – and in so doing, supporting the system that dehumanizes themselves and everyone else. It’s quite a trick, really. The system perpetuates itself by keeping everyone addicted to the matrix of white supremacy and its inherent caste system, all the while causing them to think they are upholding their own values.

Anti-racism provides white people with the daily practices that align behavior with values.

At different developmental stages on the path of anti-racism, values change. This can be observed in shifts that happen as a white person proceeds in their anti-racist identity development. For example, when a white person no longer laughs along with other white people at racist jokes in order to maintain the comfort of the status quo. And further on in development, a white person says something about the joke being racist, regardless of the reactions of others. It becomes more comfortable to say something than to remain silent.

When a white person begins to align daily practices with a value system of anti-racism, equity, humanization, and freedom from systems of oppression, an internal mass grows that becomes a place from which new choices can be made. Choices aligned with inherent values become the compass guiding a person away from the comfort of positionality and into a different quality of comfort. While anti-racist development begins as discomfort, gradually it becomes far more uncomfortable to bite one’s tongue for the status quo than to speak the truth that humanizes us all.

If the idea of naming, examining, talking about, and owning the racism that is undoubtedly conditioned into us as white people feels uncomfortable – that’s okay! Anti-racist values guide us toward entering the problem of racism humbly and honestly rather than allowing our position in the caste system to keep us hidden. The kind of pain felt when facing those parts of us brings is the pain of transformation from living on the surface of yourself, just a reflection of the status quo, to being real. This is an opportunity to join BIPOC people in the racial reality that has been their lives by seeing our own positions in the hierarchy and choosing to dismantle its fabricated infusion in us.

In the book, The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams Bianco, the stuffed rabbit asks the old skin horse if it hurts to become real. The elder speaks the truth and says “Sometimes.” But he adds, “When you are Real you don't mind being hurt.” When we make the decision to enter the problem, to face the racism we were born into, and to do the work to dismantle it, we are choosing to become real. Hypocritical positionality values can’t guide us to anything meaningful. Practicing anti-racism within ourselves, in our families, and in our communities helps us understand deeply what we are saying when we admit our racism. We are saying, “I am real. I don’t need to hide behind my caste position. I can own this so that we can see it and begin the work to dismantle it.” Being real like this means we are seeking connection with others. We are ready to move forward.

Beautifully written. <3