Memorial Day: A New Way of Remembering

- Kyrai Rose, Ph.D.

- May 29, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 28, 2024

My daughter and I had the honor and privilege of attending a song circle led by Aaron Johnson, co-founder of Holistic Resistance and the C.U.T. (Chronically Under Touched) project, and his brother, Travis. Aaron invites participants at his circles to see tears and singing as the same action. He encourages joining the circle even if you don’t know the words and even if you are off pitch. He asks people to try new things along with others. He supports bravery in joy and in grief. Importantly, Aaron also invites remembering. He invites us to look at our history as a country and remember the horror of lynching and the effects of violence against Black bodies. He artfully grounds people in the practice of singing with emotion, and then reminds them to bring that practice, with care and consciousness, to the things we have been taught not to remember. He reminds white folks to not out-grieve the griever as we stand together, remembering lynching in our country as a celebrated practice among white folks, with children included in this evil done by humans. He provides a container, woven with song and story, that humanizes properly all of the people present, and paves a shared road forward in healing. This is the type of Memorial Day that inspires evolution.

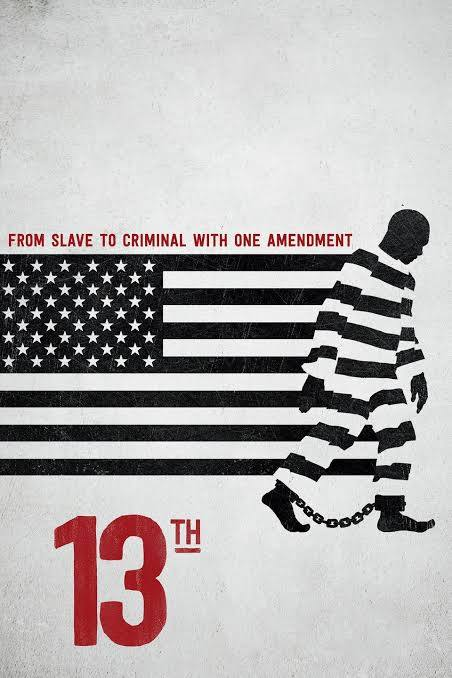

Trauma and memory have a unique relationship. Our brains remember in fragmented ways after trauma. Memories split into thinking, feeling, and instinctive memories. Usually, the thinking brain has memories in only pieces or shadows of images in order to preserve one’s ability to move on with everyday life. This is true at the personal level but also at the collective level. Our current society in the United States is one that is grappling with the trauma of terror against Black, Indigenous, and People of Color for centuries. Our politicians are fighting about what parts of history will be taught and from whose perspective. White supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks, 2012) is being named openly more often. Some young people are not so easily buying into the lies their parents believed about the myth of meritocracy. Brilliant and steadfast people are sharing their creativity, their ways of healing, and their grief processes. We are hopefully starting to feel in our bodies what we must remember – what we must put together in order to understand where we are and where we are headed and how we can go together.

The times at which we have arrived together hold much potential for transformation. In recovery circles there is a saying, “you have to feel it to heal it.” Over the years in anti-racist conversations or classes, I have observed and participated in discussions about the common places us white folks get stuck in the process of anti-racist identity development. It usually has to do with guilt, shame, or a feeling of futility – like the problem is so big, people feel lost about where to start or how to make a change. We have to feel it to heal it. We have to remember and weep, sing, and story our way through those feelings. Those stuck places point strongly to our conditioned weakness as white people. We have been taught to fear the uncomfortable and hide behind privilege and power so that we don’t have to ever face the discomfort of looking right at the horrid legacy left by white ancestors in our country. The fact that we as white people have the choice of whether or not to face that history, whether or not to remember, whether or not to tell the stories to our children, whether or not to feel the emotions IS the epitome of privilege.

In my doctoral program at Western Michigan University, we were commonly required to face the discomfort of whiteness and the pain and division it causes among people. I remember a class period in our advanced multicultural course during which a colleague brought in a book that was page after page of photographs of lynchings of Black people. Quietly, we passed the book around and looked. Together, in a multiracial classroom of doctoral students, we sat and looked. Some of us cried. Some of us wondered about the different experiences in that room, and how our different identities caused us to meet those images from distinctly different perspectives, connected to distinctly different histories, family stories, and inherited memories. We felt the discomfort of facing it, and we faced it together, even though our discomfort was unique to our identity and conditioning. We remembered together. We didn’t have someone leading us with the skill of Aaron Johnson, but we had the experience of building capacity in ourselves to be with reality together.

The United States nostalgically remembers wars and people who died in them. I understand many of the people who have served in the military did so out of a sense of honor and wanting to do something for their country. What I write here is not meant to disrespect anyone’s sacrifice or sense of service. Rather, I suggest that the value system that prioritizes that type of Memorial Day may be archaic in terms of what will help us heal from collective trauma. Many served because they had to, and many served because they saw the military as a way to go to college or support a family in times of need. But war is the most violent and destructive activity ever engaged – for human bodies and for the earth. Let us remember that. For me, Memorial Day forgets the understanding that war is sociopathic in nature. War, like white supremacy and racial violence, works against wellness, and causes far-reaching trauma.

We get nowhere without remembering what has happened and how it directly relates to our situation today in this world that is more divided than ever. Memorial Day could perhaps shift to become a day of collective grieving the horrors of the past and present, together in a shared reality that has no need to look away. We can begin to redefine wellness to reduce the need for escape into privilege and division. We can extend our creative, emotionally-rich practices to help us move away from the unrealistic expectation of an absence of symptoms of distress. Perfectionism-based ideas of wellness try to keep us on a treadmill to reach a life that will be without suffering. But living a human life includes suffering – not as a signal of failure, but as an inherent part of being a person developing through linear time with a lot of other people.

Trauma healing involves learning to stay in our bodies lovingly to help find the way through triggers. These practices gently remind the nervous system to repattern to safety and ease, and we are eventually able to rise to friction or conflict productively as needed while returning flexibly to a state of balance. It takes practice. The trauma we share due to our tumultuous and treacherous history means we have some road to walk before we will fully understand the ways we have been impacted. More road will have to be walked together as we discover ways to connect while we heal. And more road, still, will be walked as we find a new story that has no need to erase or minimize the story of our past because we will have learned to walk together.

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told

them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer

them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes

most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they ask -- and rightly so -- what about

Vietnam? They ask if our own nation wasn't using massive doses of violence to solve its

problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I

could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos

without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today --

my own government....

~Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Beyond Vietnam Speech

Visit Aaron Johnson’s website, Holistic Resistance

https://www.holisticresistance.com/

Comments